Welcome to Yorkshire

Inspiration • March 7th, 2025

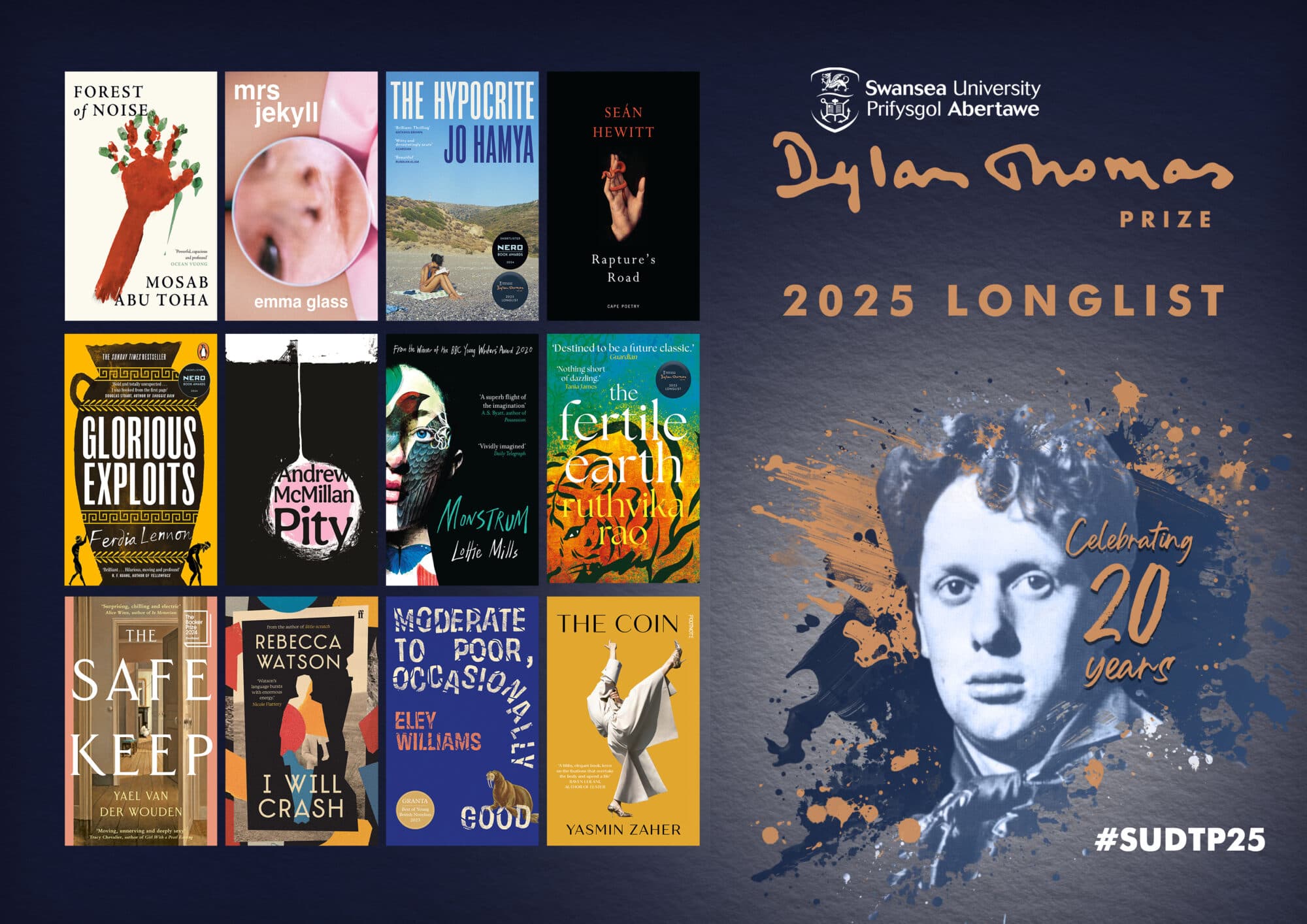

|Andrew McMillan’s literary voice is deeply rooted in the rhythms, landscapes, and language of South Yorkshire. Best known for his award-winning poetry, McMillan has now turned his keen eye and lyrical precision to fiction with Pity, a novel that spans three generations of a Yorkshire mining family. Longlisted for the Swansea University Dylan Thomas Prize, Pity is both an elegy for a lost way of life and a testament to resilience, capturing the everyday struggles and enduring spirit of a community in South Yorkshire.

In this interview, McMillan reflects on how his Barnsley upbringing has shaped his writing, the challenges of capturing authentic regional voices on the page, and why stories like Pity resonate far beyond South Yorkshire:

How has your upbringing in Barnsley shaped your writing, both thematically and stylistically?

I’m not sure about stylistically, other than I think there are certain rhythms, and certain ways of saying things which probably creep into the way I organise sentences and phrases- I write in the same cadence I speak in, in the way I hear and heard others around me speak as well. Thematically, I was raised to believe that where I was from was worthy of literature, so it was never so much a question of ‘why Barnsley’, but ‘Why Not Barnsley'

Yorkshire has a rich literary tradition, from the Brontës to Ted Hughes. Do you feel connected to this tradition, and if so, in what way?

I’m linked to it in a direct familial way through my dad, in a very obvious way, but more than that I think whatever we write, is always in conversation with everyone who’s come before and who has written about and through and of Yorkshire, seeing it as what it is, which is a crucible of endless possible stories and characters.

Pity is set across three generations of a Yorkshire mining family. What inspired you to explore this particular history, and did you draw from real-life stories?

I think in order to write about and of Barnsley, then that aspect of history seemed vital to include, and by looking across generations, it was possible to chart the changes and similarities across the shifting decades. Partly, in very specific descriptions of walking to the allotment, and key details such as that, I was thinking of my maternal granddad, and the pit disaster which is referenced is a real one, but really its the story of a town, not the story of any real individuals.

How important was it for you to capture the unique voices and rhythms of Yorkshire speech in Pity?

I think it’s very important to do it, but authentically, and it’s potentially harder than it seems to faithfully replicate dialogue and dialect on a page which doesn’t lead to a reader doing a bad impression in their mind as they move through the chapters. So the way for me to capture it was in individual words, in certain rhythms of speech on the page, in phrases which I’d heard and wanted to pay homage to within the book

What does it mean to you to be recognized for such a prestigious international literary award?

It’s a really great honour, not just for myself but for the book and the story I really wanted it to tell. This is, as you say, an international award; so often the story of places like Barnsley are dismissed as being purely local, or only relevant to that one individual place. But the story of Barnsley is the story of so many parts of the nation, of Europe, of the U.S.A- the story of Barnsley has international relevance and implications, and that’s why it feels so nice for it to be recognised in this way.

You’re an acclaimed poet. How was the process of writing a novel different, and did your poetic background influence your prose?

It’s a lot more words! There’s also the scope of what’s required, in rebuilding and editing. So editing a poem is really focussed, almost like keyhole surgery, whereas to edit a novel is a constant process of dismantling and rebuilding- the architecture of what’s required is so much bigger. I think I’ve always had the same desire for something plain and stripped back, and I tried to carry that across from the poetry into the prose.

Do you feel that voices from South Yorkshire are gaining more recognition in contemporary literature?

I hope so, though there’s still a way to go. I’ve recently started the Tempest Prize, in collaboration with New Writing North, which aims to find an unpublished LGBTQ+ Writer from the North of England. Small things like that help, but also we need to continue to build a national recognition that we all benefit when our collective culture is drawn from every town and village in every part of the country.

With the paperback coming out in February 2025, are there any new reflections you have on the book since its initial release?

It’s been really lovely to meet so many readers, and learn things I didn’t know about the book from conversations I have with them. I think I’ve grown more confident in how to talk about it too.

Are you currently working on any new projects, and will Yorkshire continue to play a central role in your writing?

There’ll be some new poetry in the not so distant future, and then perhaps a new prose book too; Yorkshire, and Barnsley will always be central to that, because they’re always so central to me.

For those eager to experience McMillan’s powerful and evocative storytelling, Pity is now available in all formats and at all major booksellers and independent bookshops. Whether you’re drawn to its rich sense of place, its poignant exploration of family and history, or its beautifully honed prose, Pity is a novel that lingers long after the final page.

Yorkshire Team

The Yorkshire.com editorial team is made up of local writers, content creators, and tourism specialists who are passionate about showcasing the very best of God’s Own Country. With deep roots in Yorkshire’s communities, culture, food scene, landscapes, and visitor economy, the team works closely with local businesses, venues, and organisations to bring readers the latest news, events, travel inspiration, and insider guides from across the region. From hidden gems to headline festivals, Yorkshire.com is dedicated to celebrating everything that makes Yorkshire such a special place to live, work, and visit.

View all articles →

Comments

0 Contributions

No comments yet. Be the first to start the conversation!